Role of Hydration in Ion Transport and Separations

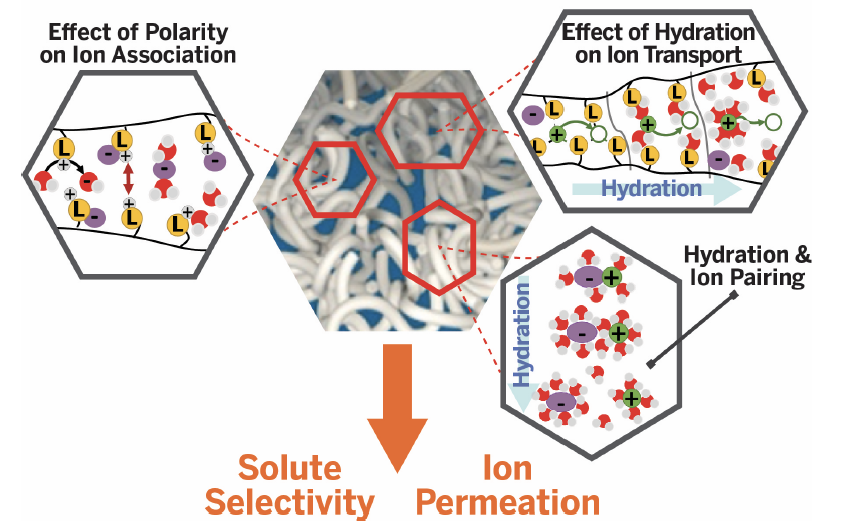

Fig. 3.1. GAP B will unravel the impact of hydration on ion transport spanning dry to wet systems, including ion pairing/association in hydrated polymer systems.

GAP B Co-Leaders

-

Benny Freeman

Director

GAP B Co-Leader

GAP C Co-Investigator

-

Rachel Segalman

GAP A Co-Investigator

GAP B Co-Leader

IF Co-Investigator

GAP B Co-Investigators

-

Lynn Katz

Associate Director

GAP A Co-Leader

GAP B Co-Investigator

GAP C Co-Investigator,

IF Co-Investigator

-

Venkat Ganesan

GAP B Co-Investigator

GAP C Co-Investigator

-

Graeme Henkelman

GAP A Co-Investigator

-

Chris Bates

GAP B Co-Investigator

-

Raphaële J. Clément

Gap Attack Platform B Co-Investigator

Problem Statement

Ion transport is central to both hydrated polymers for water filtration and dry polymers for electrochemical applications such as batteries. While remarkable progress has been made in the development of polymeric battery electrolytes and hydrated membranes for both desalination and energy applications (e.g., fuel cells, electrolyzers, and solar fuel generators), further progress hinges on developing fundamental insights into mechanisms of ion solvation/solubility and diffusion that are the foundations of ion permeability and ionic conductivity. As shown in Fig. 3.1 (above), developing this insight requires bridging understanding among both dry and hydrated membranes. Based on our success in developing ion selective membranes, we will create new design paradigms for ionic separations and develop an improved understanding of the role of hydration in the physics of ion transport. Furthermore, many membranes (e.g., RO membranes) bear charged groups, such as carboxylic acids and amines, in confined, low water content environments, where much less fundamental information is known, relative to aqueous solutions. The dissociation of these charged functional groups determines charge density in the RO membranes and, in turn, Donnan exclusion and, therefore, impacts ion rejection (i.e., selectivity) of such membranes. The impact of ionic strength, background solution complexity (e.g., mixtures of solutes and ions) on protonation/deprotonation, complexation, and ion pairing have been well studied in aqueous solution. In contrast, our knowledge of such interactions among solutes and solute/polymer functional groups within polymers is still lacking. The importance of continuum level parameters (e.g., ionic strength and dielectric constant) on these interactions has been identified in numerous studies, but robust models for predicting the influence of these parameters on membrane permeation and separation properties have not been fully developed for highly complex source waters. We will construct functionalized UMCP materials to understand the role of functional-group solute-solution interactions on continuum properties (e.g., ionic conductivity, water sorption, dielectric constant) in both confined and unconfined geometries. Whereas GAP A will provide insights into surface chemistry effects on ion solvation, dynamics, and affinity at surfaces at the molecular level, GAP B will focus on the role of hydration in bulk ion transport and separation, translating the molecular picture of GAP A to macroscopic membrane performance.

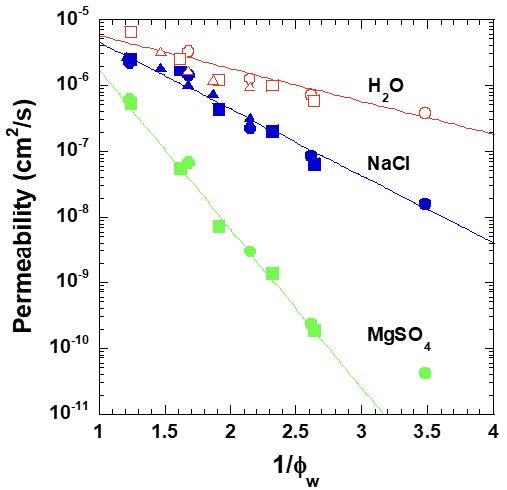

Molecular-scale permeation of water and solutes through dense, nonporous polymers controls separation properties of reverse osmosis (RO) and electrodialysis (ED) water purification membranes. Such membranes are invariably hydrated, with hydration varying over a wide range, from as low as 5 vol.% in RO membranes to 50 vol.% or more in some ion exchange membranes (IEMs) used for ED. Water and solute permeability vary by orders of magnitude with polymer water uptake (Fig. 3.2). Polymer membranes for energy applications (e.g., batteries, fuel cells, electrolyzers, and solar-fuel cells) are often chemically similar to IEMs used in water purification membranes. However, these membranes are either rigorously dry (in the case of solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs) for batteries) or much less hydrated (membranes for fuel cells, electrolyzers, and solar-fuel cells) than those used as water purification membranes. Solute transport (e.g., ion diffusion) is critical in both classes of membranes. While significant progress has been made in developing the membranes listed above, further progress hinges on a deep understanding of the fundamental origins of permeability and selectivity and how the presence of water modulates these properties. Indeed, the curation and analysis of a database of published polymer Li+- electrolyte conductivity performance (conductivity and selectivity) suggests that, with the exception of activation energy for conductivity, individual features commonly explored by this community are poor predictors of performance. Further, the performance of conventional lithium-ion batteries is limited by low selectivity of the metal cation relative to its counterion (where selectivity is parameterized by the transference number, t+). Indeed, SPE performance appears to be subject to an upper bound in permeability/selectivity similar to that which has stymied the development of seemingly unrelated gas and water separation membranes.

Further, solute size, polarity, and solvation radii are critically important for determining solute diffusion coefficients in aqueous solutions and membranes. For ions, however, their extent of hydration depends on the water content and dielectric properties of their environment, which can change enormously as membrane water content varies from dry (e.g., dielectric constant of 5-10) to highly hydrated environments that have dielectric constants closer to that of water (e.g., 40-50). Additionally, ion association (i.e., ion pairing) is favored in dehydrated, low dielectric media and disfavored in highly hydrated media. Ion association impacts effective ion size and charge, which can markedly affect ion transport rates in response to concentration gradients (e.g., RO) and electric fields (e.g., ED). Determination of individual ion diffusion coefficients from ion permeability and ionic conductivity measurements relies on the validity of the Nernst-Planck relation and on knowledge of ion association, both of which are poorly understood in hydrated membranes for water purification. Similarly, recent rigorous calculations of transference numbers for dry SPEs are substantially lower than those approximated from ideal solutions (Nernst-Einstein), presumably due to the formation of neutral ion clusters and charged ion triplets. Indeed, such phenomena have led to reports of seemingly non-physical negative transference numbers largely driven by the presence of negatively charged [anion-cation-anion]-ion triplets.

GAP B assembles a team with diverse expertise to bridge our understanding of wet (Freeman) and dry (Segalman, Clément) water-energy membranes with the goal of presenting design paradigms for future membranes. These design rules will be rooted in a fundamental understanding of the role of hydration on solute transport (e.g., water, ions, neutral molecules) in such membranes. We seek to cross-pollinate theory (Ganesan, Henkelman), characterization tools and methods (Katz, Christopher, in the IF), and materials (Bates) between the energy and water membrane communities to accelerate translation of discoveries in one field (e.g., dry membranes) to the other (e.g., hydrated membranes) and vice versa. This knowledge will elucidate the impact of water on ion sorption, diffusion, permeation, and ionic conductivity, as well as membrane structure and dynamics.

Fig. 3.2. Effect of water volume fraction, vw, on water and salt permeability in model crosslinked PEG polymers.

Research Questions

If one starts with a dry polymer electrolyte/salt system exposed to humid air, where does the first water go (i.e., to a hydration shell around the ion or to plasticizing the polymer?)

How do ion size, density, and chemistry influence this initial hydration?

How does polymer chemistry (local polarity and chemical environment around an ion) influence hydration?

What is the role of hydration on ion pairing/aggregation and ion-membrane (ligand) interactions?

How does one unravel the complexity of water content, ion concentration, and membrane chemistry/functional group binding strength on the process of salt dissolution, ion aggregation, and ion transport?

Research Approach

We propose to bridge the detailed polymer physics understanding already being applied to dry polymer electrolyte systems to the important applications of hydrated membranes. The lack of this fundamental understanding in water purification membranes stymies progress in designing highly permeable and selective membranes for treatment of highly complex water sources in RO or ED or in new applications, such as resource (e.g., Li+) recovery from highly saline brines. Similarly, our lack of knowledge of the impact of water content on pKa values of carboxylic acids in RO membranes limits our ability to predictively design high performance membranes based on these ubiquitous functional groups.

In polymer electrolytes, ion conductivity is achieved through salt dissociation into unpaired cation/anion charge carriers and subsequent transport/diffusion of these ions through the polymer. These two steps strongly depend on several factors, including cation solvation thermodynamics, polymer backbone dynamics that control solvation site connectivity, and the rearrangement of covalently tethered coordination sites (i.e., ligands) with metal cations. As a result, these phenomena and the relationships between ligand bond chemistry and the physics of polymer chains have been widely studied in dry polymer electrolytes aimed at designing highly conductive, selective polymers for energy storage devices. In dry polyelectrolytes, combined Pulsed Field Gradient (PFG)-NMR spectroscopy and electrochemical measurements have demonstrated that ion aggregation and pairing profoundly affect these key metrics of electrolyte performance. The performance of hydrated ion exchange membranes (e.g., crosslinked poly(styrene sulfonate), quaternary ammonium functionalized poly(styrene co-divinyl benzene)), functional groups in RO membranes (e.g., benzoic acid, aniline) that are frequently implemented for water purification can also be strongly affected by ion dissociation (i.e., formation of ion pairs). However, molecular scale understanding and design rules like those employed in the dry polyelectrolyte context have not yet emerged.

We propose to deconvolute the roles of hydration, relative ion size, free volume, and polymer segmental motion on ion conductivity, permeability, and selectivity to yield better future systems, both wet and dry. The hydration shell surrounding an ion affects both its radius and diffusion coefficient as well as the strength of its interaction with membrane ligand groups. Similarly, membrane water content influences both the segmental motion of the chains and the free volume of the system as a whole. In dry polyelectrolyte systems, ion conduction is generally tied directly to polymer segmental motion, so most ion conductivity can be explicitly normalized via Vogel-Tammann-Fulcher (VTF) scaling, but the degree of salt dissolution/ion aggregation is both limited and critical to achieving high conductivities and selectivities.

We hypothesize that small amounts of hydration promote salt dissolution and result in the formation of a hydration shell around the ion of interest, but ion diffusion is controlled by local polymer segmental dynamics. In highly hydrated systems, ion diffusion proceeds through highly hydrated regions of the membrane, with the polymer chains serving as essentially immobile, fixed obstacles that increase tortuosity and reduce the available area for transport240. In both cases, the concept of free volume is often used to rationalize observed trends of ion diffusion coefficients with respect to ion size and membrane water content. Additionally, variations in water content of hydrated membranes strongly influence ion-ligand interactions, causing ion solubility and diffusivity to vary significantly in poorly predicted ways. M-WET’s earlier studies of selective ion transport 12-crown-4 (12C4)-functionalized membranes demonstrated that Li+ ions, which bind selectively to 12C4 groups in nonaqueous media, exhibited little affinity for 12C4 groups in hydrated membranes. Instead, Na+ ions bound strongly with the 12C4 groups, markedly impeding their diffusion and resulting in the highest Li+/Na+ selectivity reported to date for dense, hydrated polymer membranes.

In this GAP, we will leverage both our recent success in developing selective functional groups and the tools used by both the dry and wet polyelectrolyte communities to understand the role of hydration on ion transport and create new design paradigms for ion selective membranes. This effort is divided into two efforts: Project 1 will seek to understand the role of hydration on ion association and develop functional groups that both facilitate ion dissociation/transport as well as selectivity. Project 2 focuses specifically on the role of local polarity on proton and ion affinity and the associated thermodynamic parameters that govern separation, particularly in confined environments.