Structure and Dynamics of Water and Solutes Near Interfaces

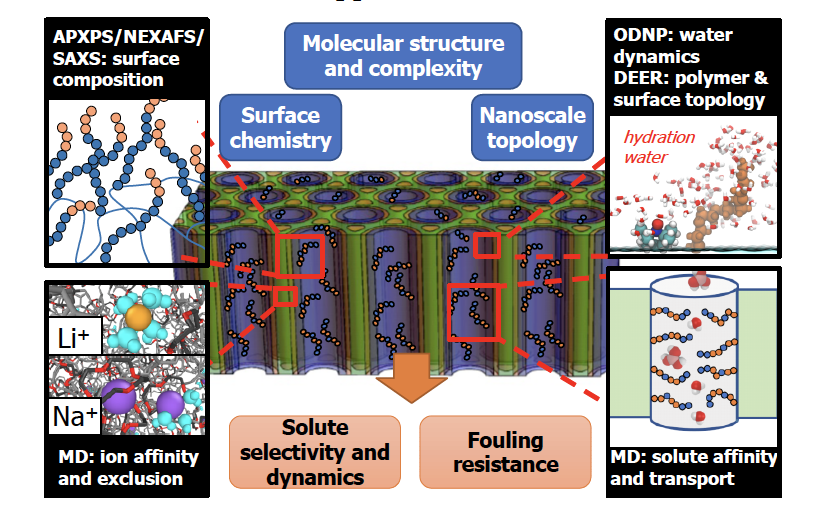

Fig. 2.1. GAP A will integrate state of the art spectroscopic tools to measure surface chemical compositions, including solutes, as well as ODNP to probe water dynamics and double electron–electron resonance (DEER) spectroscopy to quantify surface polymer conformational landscapes. Complementary MD simulations will compute ion and solute affinities/activities at surfaces, as well as water structural, thermodynamic, and dynamic properties.

GAP A Co-Leaders

-

Lynn Katz

Associate Director

GAP A Co-Leader

GAP B Co-Investigator

GAP C Co-Investigator,

IF Co-Investigator

-

Scott Shell

Associate Director (UCSB)

GAP A Co-Leader

GAP A Co-Investigators

-

Rachel Segalman

GAP A Co-Investigator

GAP B Co-Leader

IF Co-Investigator

-

Craig Hawker

IF Co-Investigator

-

Graeme Henkelman

GAP A Co-Investigator

-

Ethan Crumlin

GAP A Co-Investigator

IF Co-Investigator

-

Greg Su

GAP A Co-Investigator

GAP C Co-Investigator

IF Co-Investigator

Problem Statement:

Our understanding of membrane processes and phenomena, including transport, partitioning, selectivity, and fouling, crucially depends on knowledge of the interactions of water and solutes with membrane interfaces to permit the design of functional surfaces with targeted solute partitioning, fouling resistance, and selective solute transport. Conventional approaches to membrane design, which rely on heuristics to adjust surface hydrophobicity, charge, and roughness, have faced barriers in simultaneously engineering desired antifouling, transport, and permeability-selectivity properties. Even advances using heterogeneous surfaces rely on heuristic interface design. For example, recent efforts suggest that amphiphilic surfaces with hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions may achieve both fouling resistance and release, while other studies suggest that highly hydrophilic zwitterionic surfaces confer strong fouling resistance through the formation of a tightly bound and networked water hydration layer. In both designs, however, the molecular scale chemical and structural properties responsible for fouling resistance are not clear, and hence the optimization and scaleup approach remains heuristic. For example, what property defines a “tightly bound” hydration layer? To effectively inform membrane surface design, we must understand which surface properties define interactions and non-interactions between solutes and surface functional groups at the nm-scale. Relevant interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, van der Waals interactions, etc., will impact hydration layers. Specific chemistries such as charged surface groups can tune hydration water and solute affinity, and surface softness and topology impact local surface energies. Without a foundational understanding of the molecular mechanisms underpinning water, solute interactions/binding, and surface solvation thermodynamics, current membrane design remains bound to Edisonian trial and error approaches.

The objective of GAP A is to develop this critical missing fundamental picture of surface-water and surface-solute water-mediated interactions and identify the specific molecular mechanisms underlying solute affinity (Fig. 2.1 above). We focus on heterogeneous interfaces that remain poorly understood compared to the large body of work that has characterized highly idealized, homogeneous interfaces. Quantitative studies of heterogeneous surface systems will generate design rules for macroscopic and molecular-scale surfaces to:

engineer surfaces with targeted hydration properties,

control solutesurface affinity, and

manipulate water and solute affinity and repulsion, identifying conditions that optimize solute/ion adsorption (fouling-resistance) and desorption (foulant release, membrane cleaning).

Together, these learnings will inform the computational inverse design of surface chemistries with tailored properties. Such knowledge will also have wide-ranging influence on many other challenges, including, for example, the design of active functional surfaces (e.g., antifouling, antimicrobial, biocatalysis), electrochemical energy storage, and biomolecular separations and sensors. These advances provide a molecular framework for understanding the role of hydration in ion transport in GAP B, for incorporation into membranes in GAP C, and for understanding the origins of macroscopic membrane properties in the IF.

Research Questions

We focus on fundamental knowledge gaps in understanding the response of water and solutes to surfaces at the nanometer scale, and the effect of these thermodynamic, dynamic, and structural responses on macroscopic properties of transport and solute affinity/adhesion. We address the roles of chemistry (e.g., hydrophobicity, charge), topology (e.g., polymer brush density), heterogeneity (e.g., mixed composition), and solute identity (chemistry, size, charge). Our questions focus on three levels of understanding:

How does membrane surface chemistry and topology impact the surface hydration water layer and its properties? What is the effect of surface chemistry, flexibility and topology, chemical group composition and spatial presentation on hydration layer water structure, thermodynamics, and dynamics? What defines a “bound” water layer in terms of these properties?

How does surface chemistry and topology tune the affinity, activity, and diffusivity of solutes at the interface? How do specific surface chemistries and compositions impact solute affinity? What structural or dynamical properties of the water hydration layer signal solute affinity and are important to control? How are these behaviors modulated by solute type (e.g., size, hydrophobicity)?

How does surface chemistry and topology impact ion hydration, pairing, activity, and dynamics at the membrane surface? Ions are complex solutes due to their strongly bound hydration shell, ion pairing, and long-range electrostatic interactions. How does ion hydration and pairing change near the membrane surface? How does polymer hydrophobicity, charge density, and hydration impact ion affinity and dynamics? How do complex salt mixtures and high salt concentrations alter surface-ion interactions?

Research Approach

Our unique suite of computational, synthetic, and characterization tools allow us to gain critical molecular insight to surface and interfacial interactions that control solute partitioning, transport, and fouling. GAP A will use the non-porous UMCP platform to rapidly screen the role of functional groups such as amphiphiles, hydrogen bond donors, charges, and zwitterions on water hydration and dynamics and solute interactions (Segalman, Hawker). This platform is further capable of seamlessly integrating experimental probes, and featuring the display of functional groups on various surfaces, micelles or particles in solution. Atomic and molecular scale characterization via simulation (Shell, Henkelman), advanced NMR and EPR techniques (Song-I Han), and spectroscopic analysis (Katz, Crumlin) of the thermodynamic and dynamic interactions of these moieties with MFP solutes will integrate with selectivity design in GAP B and macroscopic fouling characterization (Katz, Su) in the IF.

The importance of fouling resistance to membrane performance motivates us to understand the roles of amphiphilicity, local charge groups, and molecular complexity on surface interactions with water and potential solutes. Further, we seek to build bridges between the extensive body of literature addressing marine fouling and molecular scale fouling in membrane technologies:

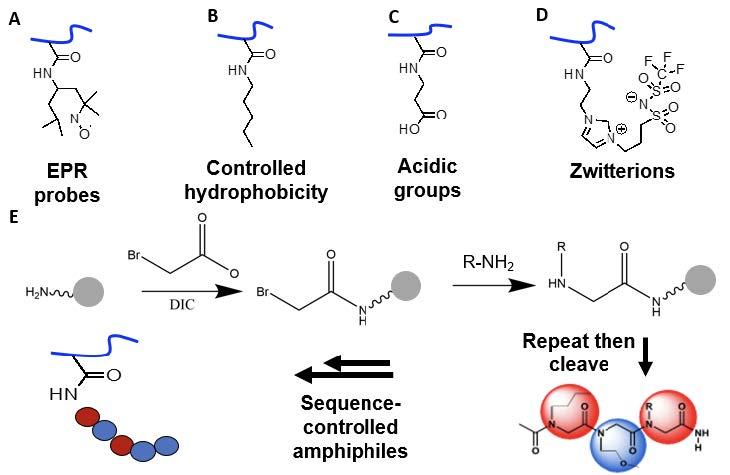

Recent advances in marine antifouling surfaces suggest that molecularly-patterned amphiphilic materials with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions present “ambiguous” surface properties that achieve fouling resistance and release, but the optimal domain length scale remains unclear. To create such patterns, we will leverage Segalman’s work with polypeptoids to make sequences of hydrophilic and hydrophobic monomers Fig. 2.2E below).

Zwitterionic surfaces have demonstrated strong fouling resistance attributed to their hydrophilicity. Such surfaces, while less controllable than peptoids, are scalable. To probe the effects of charge diffuseness, we will incorporate zwitterions (Fig. 2.2D below) with varying charge density.

2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidinoxyl (TEMPO, Fig. 2.2A below) is a promising addition for disrupting interface chemistry employed by hard marine foulers. Segalman has shown that co-attachment of TEMPO and PEG to the same backbone results in surface delivery of TEMPO, due to a directing effect by PEG in water, where it is positioned to disrupt interfacial adhesion processes of marine foulers by interfering with oxidative and radical-based reactions. Conveniently, TEMPO also enables complementary Overhauser Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (ODNP) characterization of local water properties using techniques developed by Song-I Han.

Fig. 2.2.A-B-C-D-E. Functionalization of the non-porous UMCP to impart experimental probes (A), hydrophobicity (B), charged groups (CD), and peptoids for sequence controlled amphiphilicity (E).