Project 3: Mechanics of Isoporous Membranes

Development of next generation isoporous membranes requires co-design for optimized selectivity, permeability, and mechanical properties. While much is known about the design of mechanically tough polymers, we need to understand the specific role of pores in the fracture process to design tough membranes. With this understanding, implementation of known block copolymer anchoring and other nanometer scale geometrical features to improve fracture energy, yield stress, and fracture strain is possible.

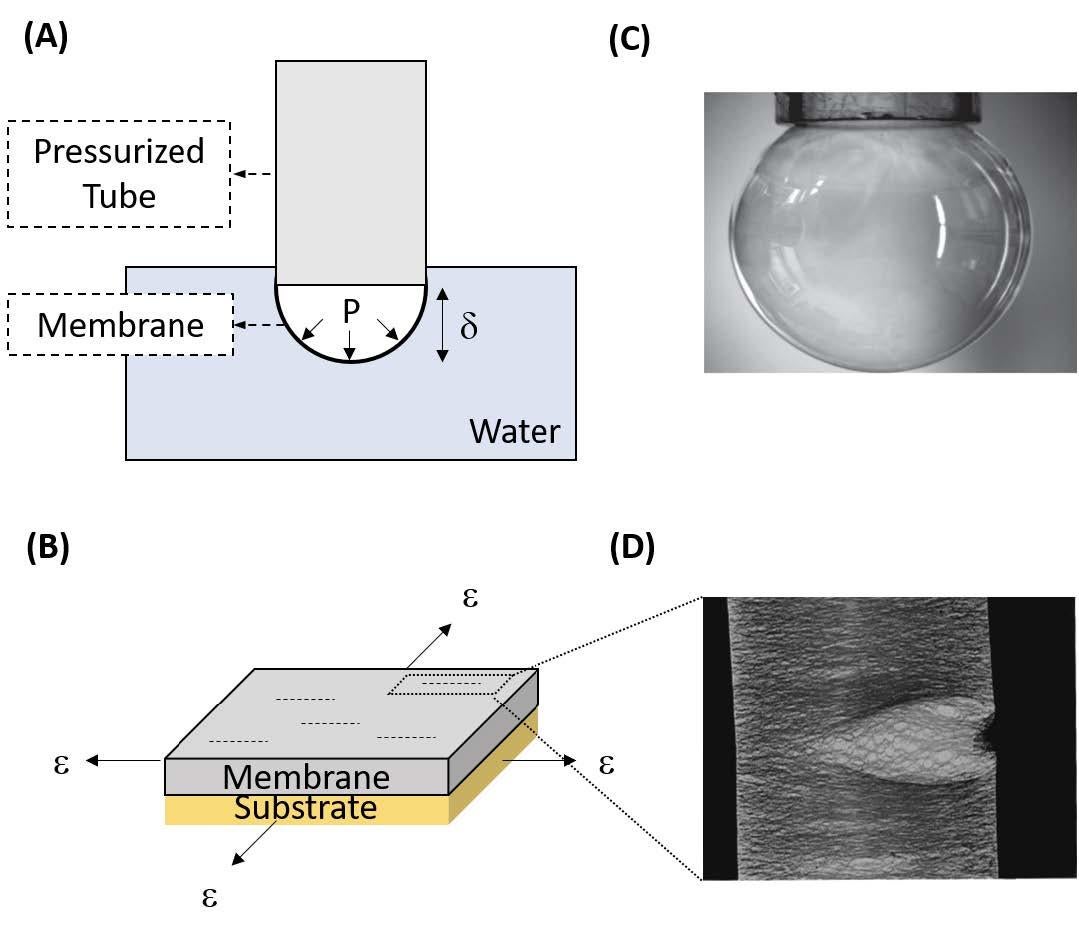

To understand the role of pore structure on the mechanical properties of membranes, a UMCP series of varying porosity will be produced by SNIPS, equilibrated in water, and inflated until failure with a membrane inflation apparatus shown in Fig. 4.5A and 4.5C (Sanoja). The resulting apex stress-strain curves will be used to validate and inform our simulations and determine mechanical properties including the biaxial modulus and work of extension until failure (Dortdivanlioglu). By identifying the critical pore size distribution at which the work of extension until failure of an isoporous membrane matches or outperforms that of a dense membrane, membranes will be prepared with improved transport properties and excellent mechanical integrity. A recent review by Long et al. argued that dense elasto-plastic materials like block copolymers with cracks of order 1 mm behave as pristine, suggesting that pore sizes from 10 nm to 1 mm should not affect the mechanical properties279. However, this prediction assumes that mechanical properties like the fracture energy, yield stress, and fracture strain are insensitive to specimen geometry and hierarchical structure. Experimental validation is required in thin, porous membranes where confinement effects and stress inhomogeneities could be important.

UMCP membranes will also be cast on deformable substrates (e.g., copper grids), equilibrated in water, and equibiaxially deformed until failure (Fig. 4.5B, D) (Sanoja, Fredrickson). By monitoring the crazing and failure strains using in situ optical and scanning probe microscopy, and SAXS during tensile testing, fracture mechanisms of membranes will be unveiled, as will be molecular designs that delay craze nucleation and growth under equibiaxial loads.

Understanding the brittle-to-ductile transition of membranes is important to prevent catastrophic failure, but membrane lifetime is often controlled by creep under fixed sub critical loads. To evaluate this transition, UMCP membranes will be inflated to a fixed apex stress, with the apex strain monitored as a function of time (Sanoja). In collaboration with the IF, we will also evolve the UMCP to include rubbery blocks within the polystyrene membrane matrix to impart compliance. Other forms of physical and chemical cross-links within the matrix will also be explored as a part of the UMCP evolution to a more robust material. Multi-scale finite element (FEM) models will complement experimental efforts to understand the role of microscopic pore structure on the macroscopic mechanical properties of UMCP membranes (Dortdivanlioglu). At the mesoscopic scale, Representative Volume Elements (RVE) of the hierarchical structure will be generated to model the pore-polymer interfaces connecting the walls of the pores with the bulk of the membrane. The bulk and interfacial properties will be informed by atomistic simulations (Dortdivanlioglu, Ganesan), and the RVEs used to construct a myriad of constitutive stress-stretch relations that describe the gradient in mechanical properties from the top to the bottom of the membrane. Integrating such mesoscopic information into macroscopic FEM models via numerical FE2 homogenization methods284 will provide a multi-scale picture of the role played by pore structure and interfacial segregation of block copolymers in the mechanical properties of UMCP membranes. Notably, this multi-scale FEM model can be used to describe anisotropic, capillary, or inelastic behaviors at the pore-polymer interface, meaning that it can both enable novel phase-field models for predicting the onset of crack propagation and aid in designing selective and permeable membranes that resist equibiaxial loads under wet operating conditions.

Fig. 4.5. Mechanical properties will be evaluated by (A) inflating (B) equibiaxially deforming membranes while monitoring (C) inflation deflection, and (D) crack nucleation and growth.